Pogonoscopus species leafhopper

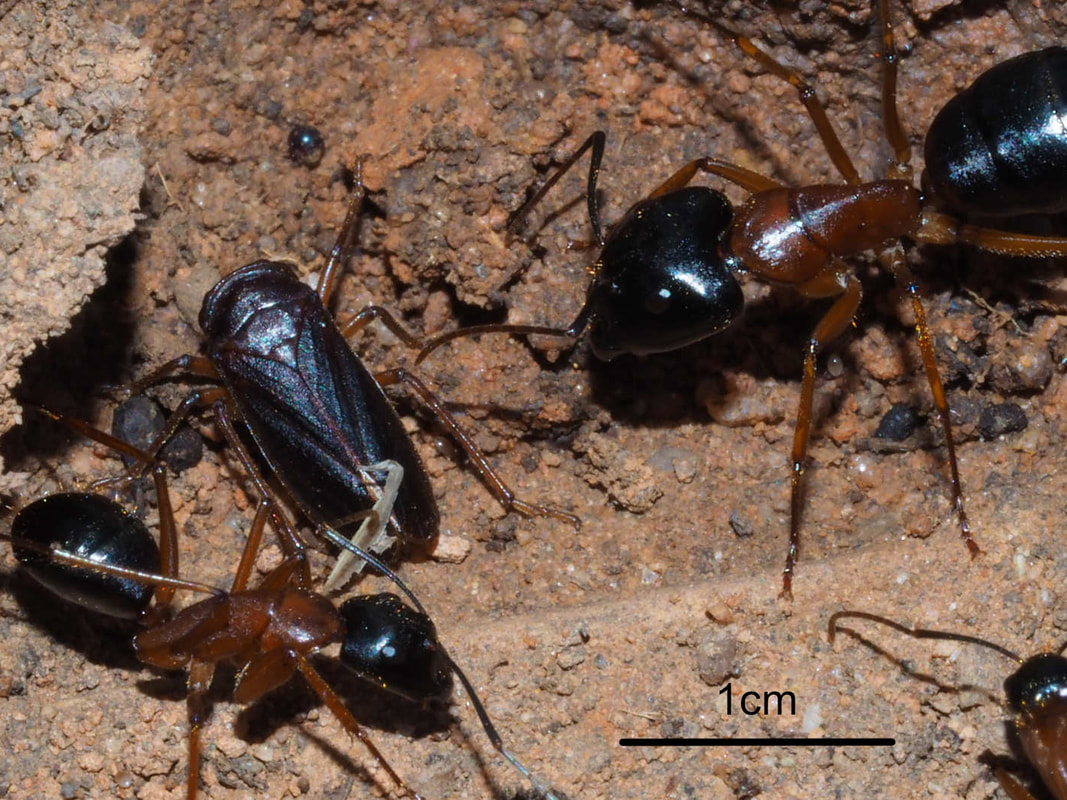

Pogonoscopus species leafhopper Serendipity is a wonderful thing. Recently I found an ant nest under a discarded cardboard box with brown leafhoppers that live with the ants. The leafhoppers ran back into the tunnels while the ants swarmed out.

According to the attached research paper, nocturnal Pogonoscopus species leafhoppers have an inquilistic relationship (word of the month = they benefit from) with Carpenter (Myrmex species) ants.

During the day, the leafhoppers shelter in the ant nest near eucalypts. At night they emerge and climb up the eucalypts to feed on sap. The ants attend them to get a feed from the the leafhopper’s rear.

Unlike other leafhoppers this species has long rear legs to enable them to climb up trees quickly, so it does not hop. They could also have little or no vision, although the ones I saw very quickly moved away.

from light

The ant/leafhopper relationship is species specific and these leafhoppers would be attacked if they entered the wrong nest.

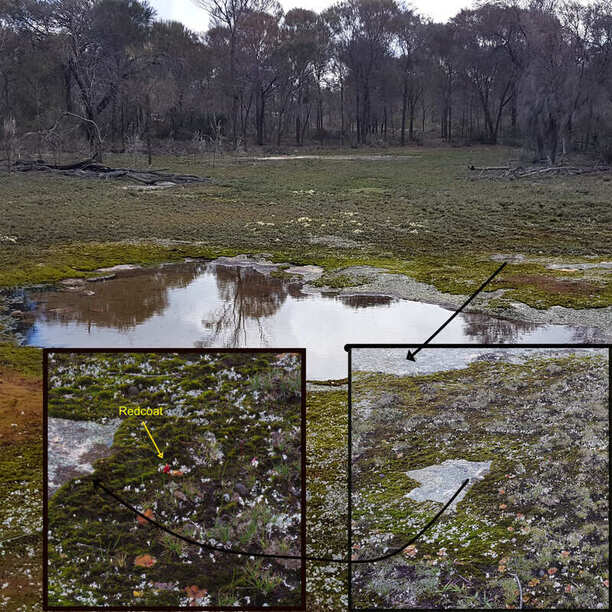

Carpenter ants are active at night, as I noticed when photographing frogs at the claypit one night last spring.

A day active leafhopper below has more typical large eyes and more vertical wings

| Reference |

| ||