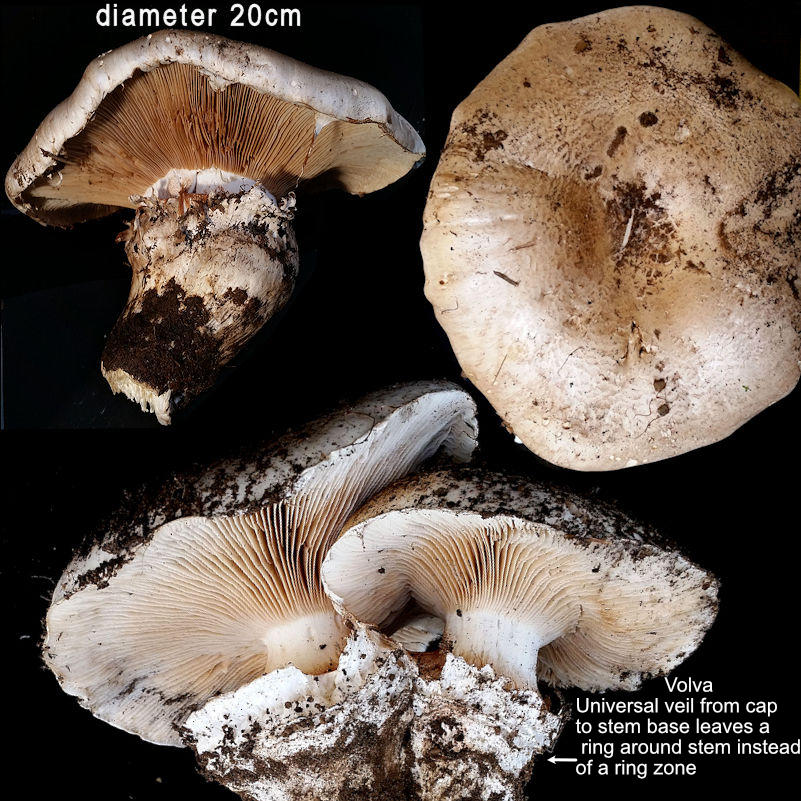

Slippery Jack Suillus luteus

Slippery Jack Suillus luteus A bolete Suillus luteus / Slippery Jack has been introduced as a mycorrizal fungus for pines. The slippery yellow bolete looks distinctly unappetising to me, but there is a bunch of local Ukranians eagerly awaiting it's appearance.