An ochre pit at Dryandra National Park is one of over 440 recorded around Australia. For a nation this large, it is a small number, hence the value of ochre as an item of trade.

Charcoal and in some areas coal was the basis of black ochre, which was crushed and mixed with a fluids such as water, saliva, blood or fat as a sticking agent.

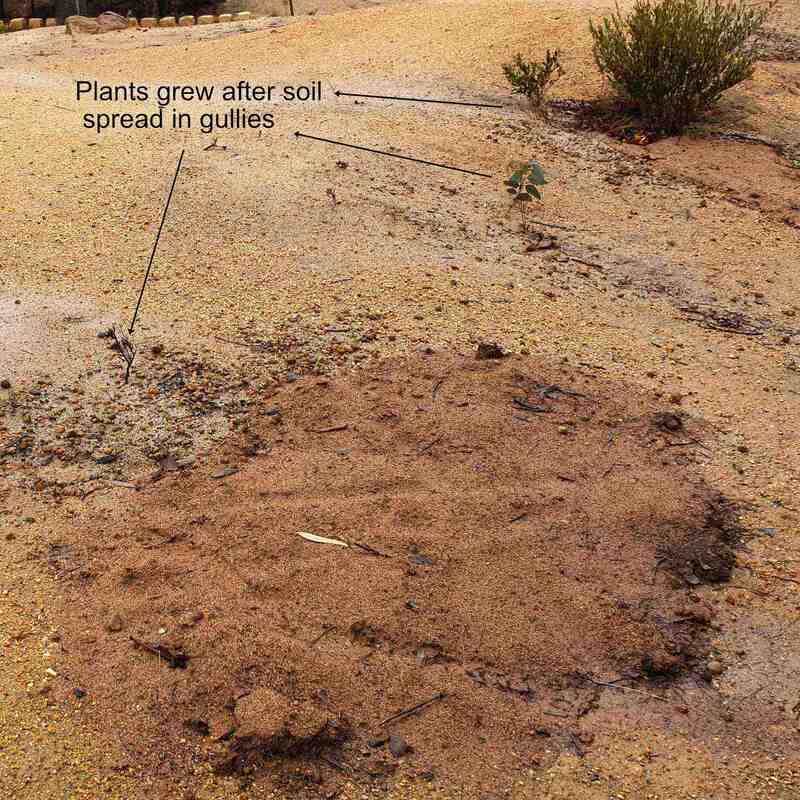

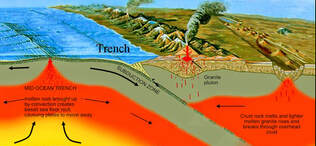

Other ochres are mineral oxides attached to a white non-cracking clay called kaolinite, particularly in subsoils in the wheatbelt and rangeland uplands. In Australia this clay has formed as a deep layer underneath mesas, which are ancient remnants of ancient lateritic land surfaces.

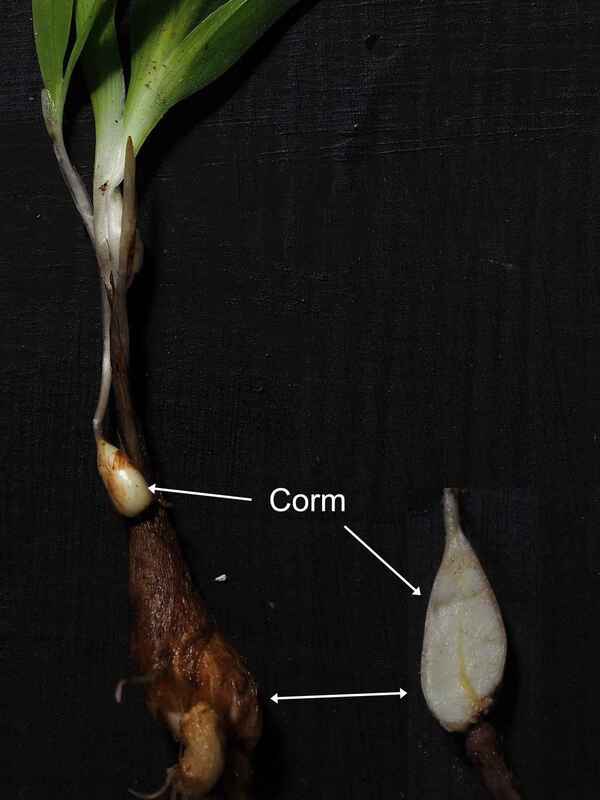

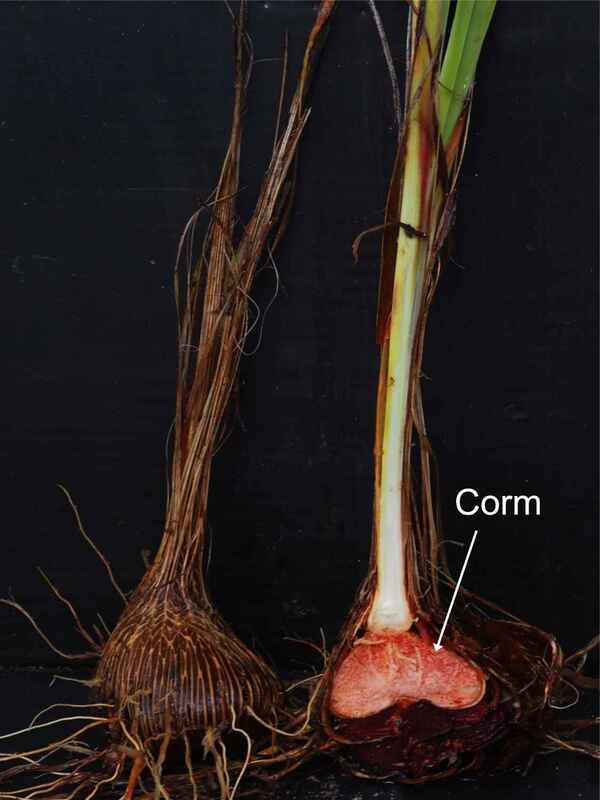

- The gravel layer contains most of the plant roots.

- The mottled zone layer is a transition to the pallid zone layer, which is stained by iron leaking down from the gravel layer.

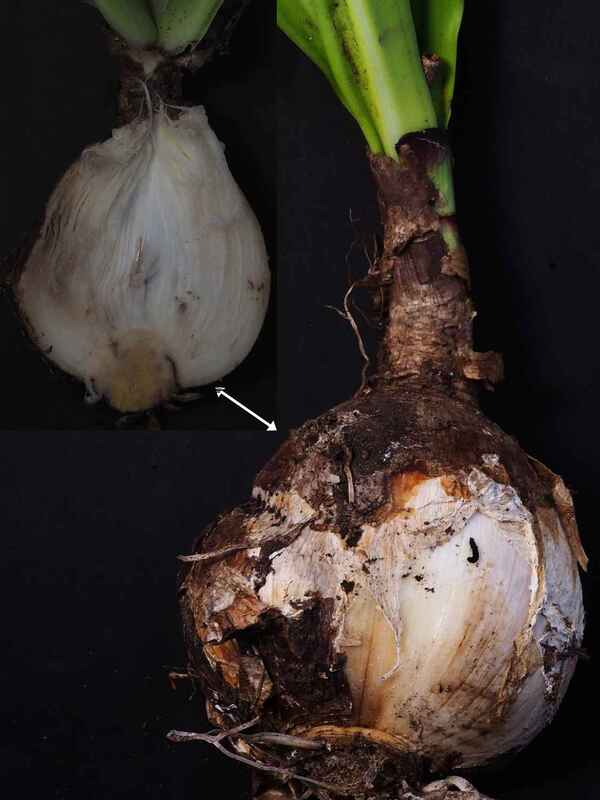

- The pallid zone layer is decomposed bedrock, which has been weathered to clay and sand, and infilled with extra clay

Electron microscope images of halloysite forming around bacteria lead on to a great story of soil development where plants lift minerals up from the depth in soil water, and microbes and fungi convert them to lateritic gravels, bauxite or clays.

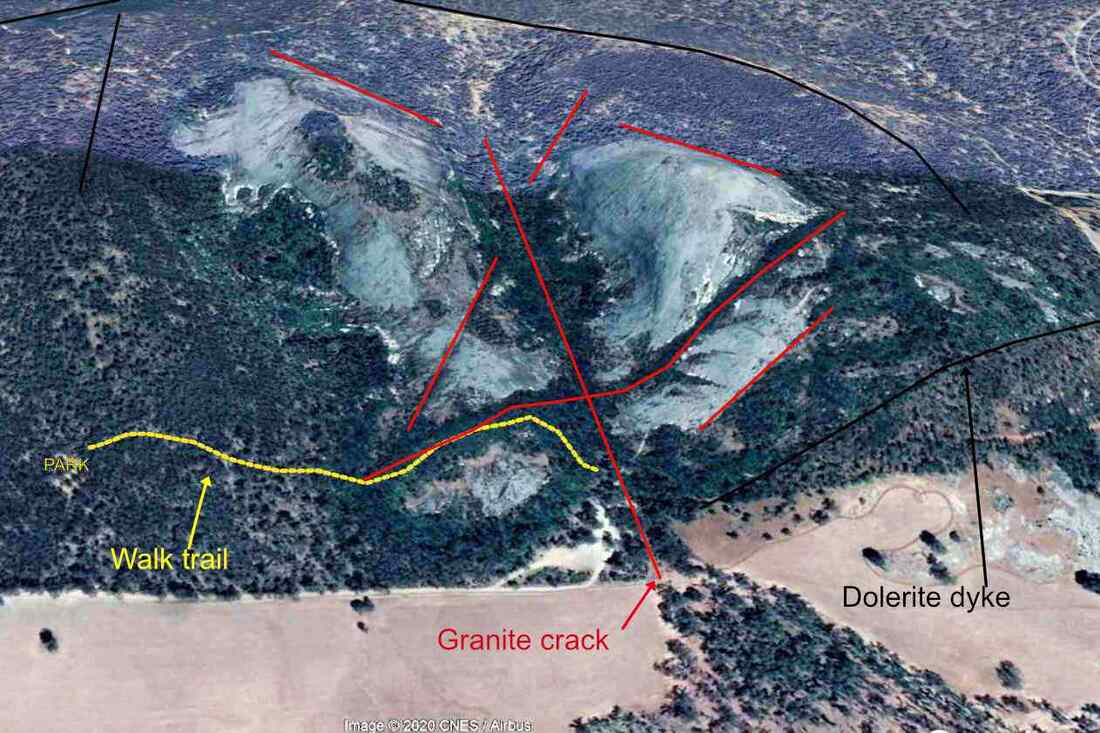

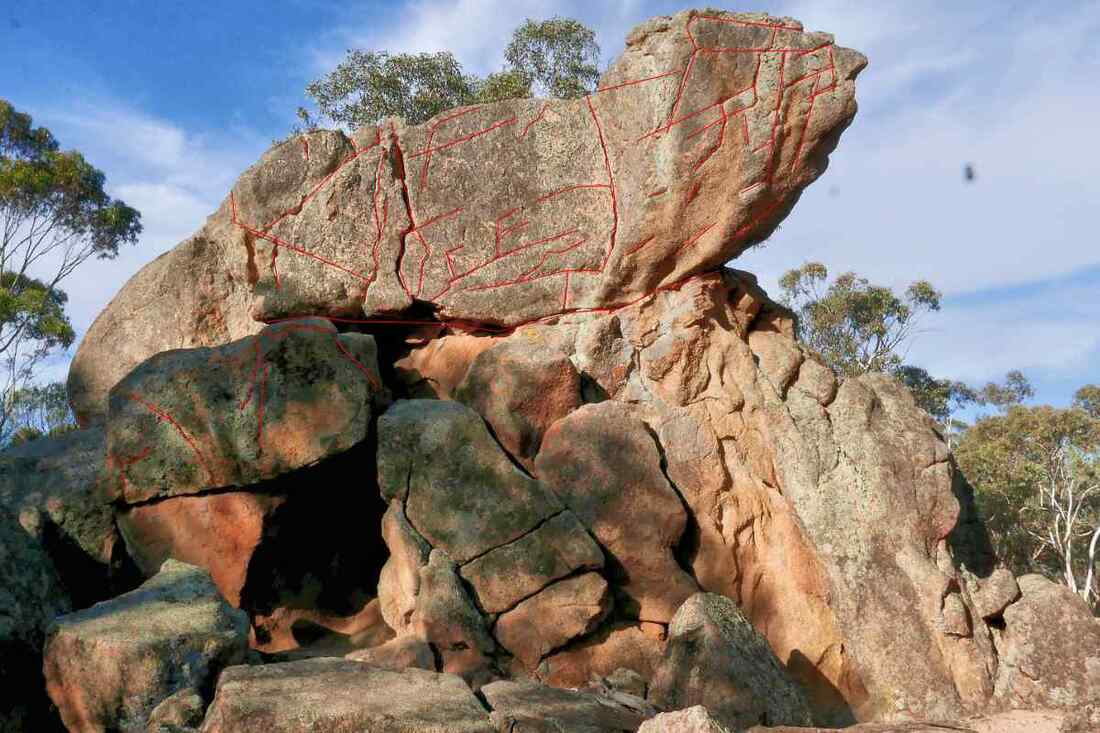

However, ochre only outcrops naturally on breakaway slopes. Granitic breakaways contain white ochre and less commonly yellow ochre (which contains an iron oxide called limonite). Red ochre contains an iron oxide called haematite which is mostly found on steep red-brown breakaways, which have formed off very iron-rich rocks such as dolerite. Green ochre (containing a nickel oxide) is rare, only being found on ultramafic rock breakaway areas such as the Goldfields.

Good ochre contains very little sand.

- Put the ochre sample in a bucket and add enough water to make liquid

- Swirl the liquid vigourously, then pour clay and water slurry off into another bucket leaving sand behind

- Leave the water and clay for a couple of days until the clay settles out leaving water above. Adding salt may help.

- Pour off the water leaving the clay slurry behind to evaporate to a creamy consistency