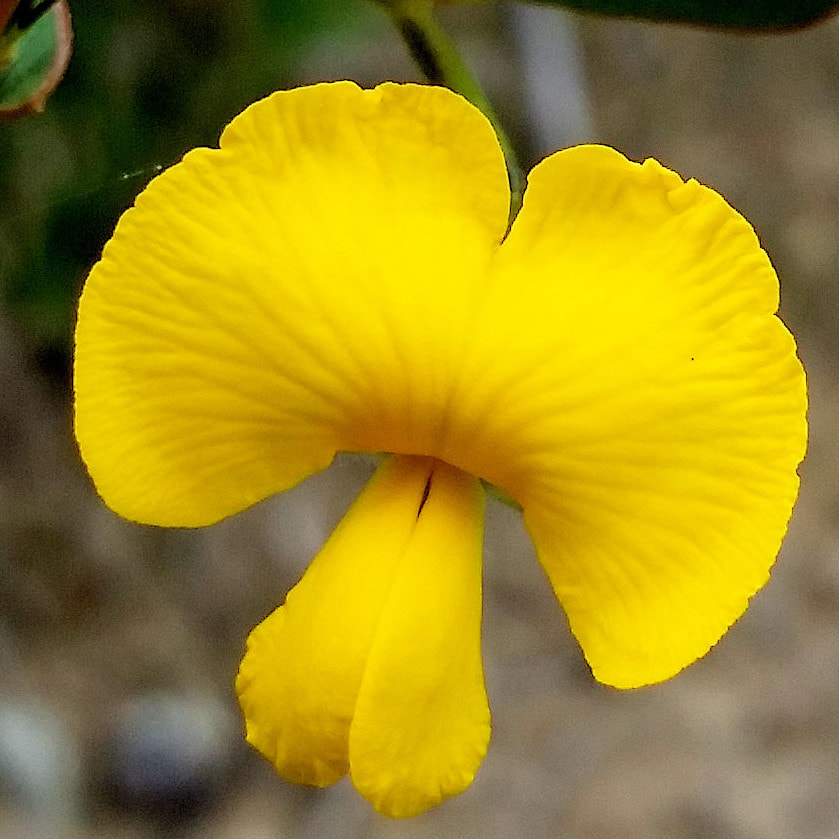

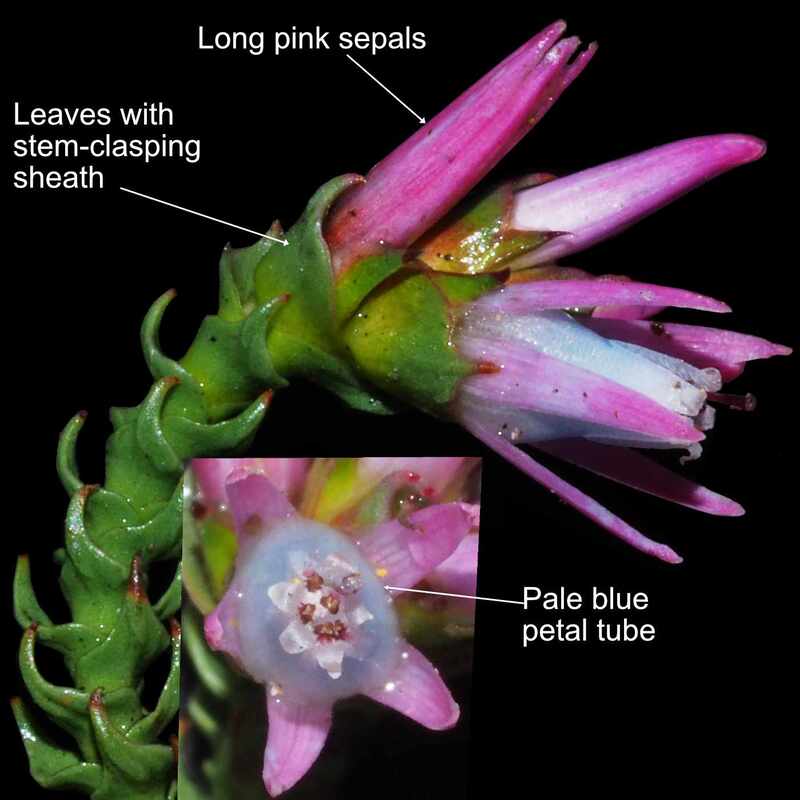

They all have five petals whose shape has evolved specifically for pollination by native bees.

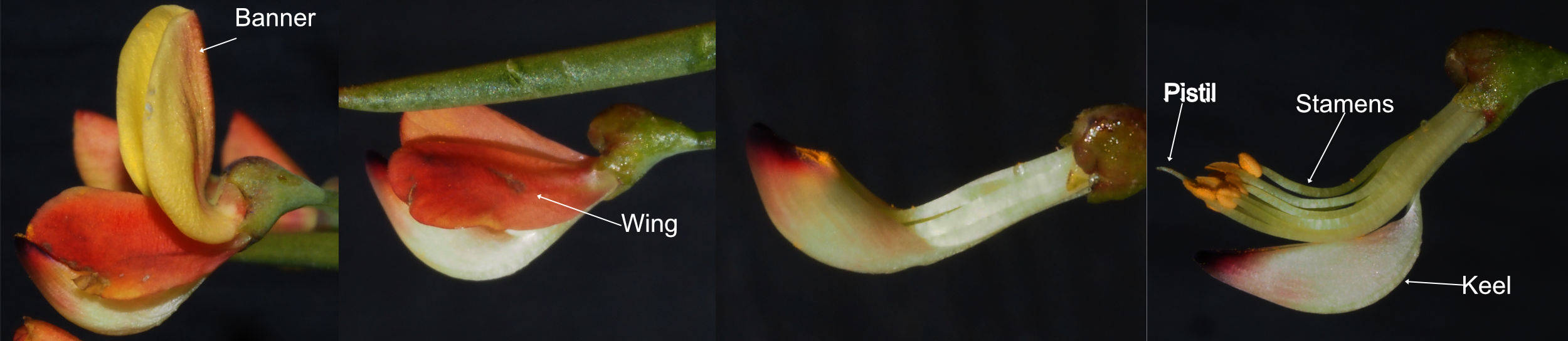

- The large top petal called a banner usually has a differently coloured 'bullseye patch' at its base, which attracts the bee to a nectar gland is. Because bees can see ultraviolet light, the bullseye patch stands out even more for them than for us. For more information see this paper.

- Below this, two sideways- aligned petals called wings project out as a landing point, and cover the stamens and pistil.

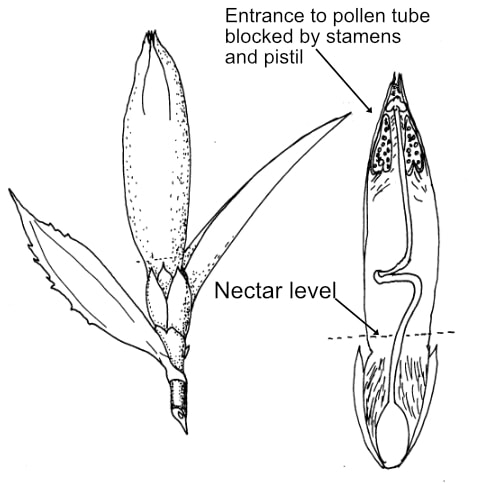

- Under the stamens and pistil is the keel, which consists of two petals, joined to form a boat - shaped base to stop insects getting at them for below.

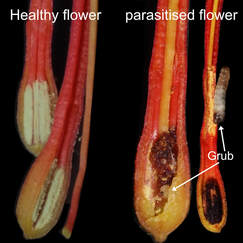

European honey bees don't play by the rules. They often steal nectar from the side of the flower. I recently saw honey bees chewing into Daviesia flowers before they had opened. The bees destroyed flowers and ate the pollen. With their overwhelming numbers, they reduce pollination and native bee numbers.

The plant can form cluster roots enables it to extract phosphorus from organic souces such as charcoal.

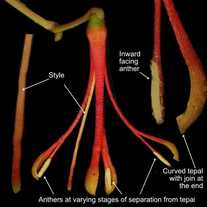

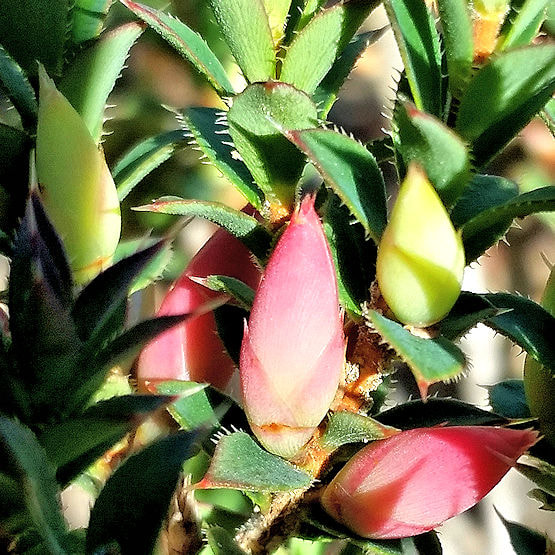

The large red flower is designed for bird pollination, presumably because birds colonise burnt areas before insects. Unlike other pea flowers,the wings don't cover the keel allowing a honeyeater to accurately place its beak to get nectar and pollinate the flower.