I am sure that many of you have lain awake at night and pondered on this problem: "Why do salt lakes occur seemingly randomly along waterways, why are they round, and why do they often have dunes on one side and a steep slope on the other?. Well ponder no more.

The answer is a bit complicated, but includes geology, earth movements, salt reserves in the subsoil, and long term climate variation.

Unlike most other countries, we do not have permeable sedimentary rocks under our soils. East of the Darling Fault the underlying rock is a huge slab of continental (mainly granitic) rock that makes an impermeable basement below the weathered layer. This has been fractured by faults and is crossed by lines of dark dolerite type rock that weathers to a tight red clay. These two redirect or block groundwater flow. Many Great Southern lakes started when groundwater has been forced to the surface where these structures intersect waterways.

In very dry periods winds would blow sediment out of the dry lake bed, causing it to become deeper, and producing dunes on the edge. When the lake was full, wind caused the water to swirl in a circular motion that cut away at the edges of the lake. Additionally, while a part of a supercontinent called Gondwana for hundreds of millions of years, Western Australia slowly eroded down to leave a relatively flat landscape.

Lake Taarblin was considerably larger when the climate was wetter 3000-4000 years ago, but the eastern side has since been infilled by dunes and interdunal salt pans.

When more water entered the soil than plants could use, salt was brought to the surface in groundwater causing salt patches. This is happening now after clearing bush for farm land, but it has also happened naturally in the past. Interestingly first Europeans in the district discovered that the existing lakes were mostly fresh, but did not fill as much as today.

You may have noticed that lakeside dunes are mostly sandy in the Western wheatbelt, but loamy with lime nodules in dryer areas. The reason for this is that lakes in the east tended to be dry and saline in arid periods with dunes created from the saline lake floor, whereas western lakes were full more often with sand washing in with the water.

You can tell the difference from the dunal vegetation. Acorn banksia (Banksia prionotes) and woody pear (Xylomelum angustifolium only occur on wind deposited sand.

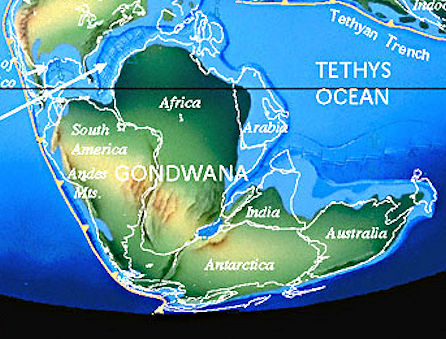

This is the story: When Australia finally separated from India on the west and Antarctica to the south, stress in the underlying basement rock caused two things to happen.

1. Great rivers used to flow south from as far north as Beacon in deep canyons to the south coast. The Antarctica separation caused the rise of a low east west ridge near the south coast called the Jarrahwood Axis that tilted much of southern WA down to the north and reversed the flow of these rivers. Resulting sluggish valleys with little slope filled up leaving a chain of lakes that only flow in a very wet year all the way to the Salt River past Quairading then the Avon to Perth.

2. The Salt River and other rivers like the Beaufort and rivers further north, were also large active rivers that flowed to the coast when India was gradually separating from WA. After the separation the Darling Range gradually rose upwards and blocked these rivers, causing them to back up as huge lakes that became the source for extensive sandplains to their south and east. A prime example is the Yenyenning lake system where the Salt River was diverted north to the Avon River.

These earth movements in conjunction with climate variation has resulted in large areas of aeolian soil in the wheatbelt. These include the Watheroo, Meckering/Cunderdin, and Corrigin/Quairading sandplains, and morrel blackbutt loams in the Lakes District.