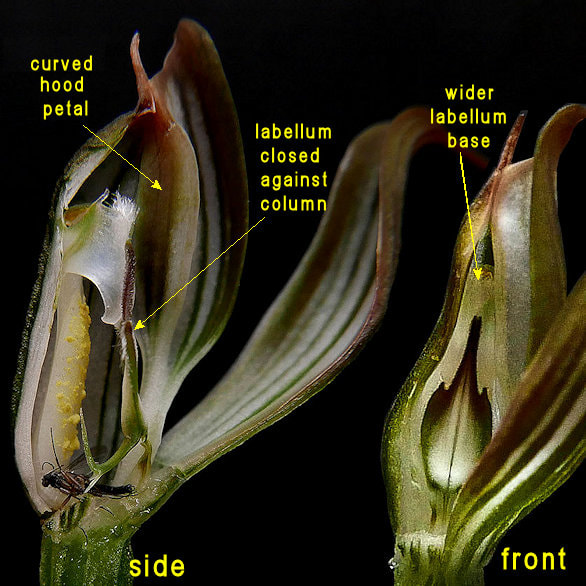

After dissecting greenhood orchids to see how they trapped insects I moved on to shell and jug orchids that have a more open appearance. In the shell orchid image below one can see that the lower two sepals are upswept rather than being down to form a landing platform, the hood is more open, and the labellum is much skinnier. A few deft slices of my trusty scalpel revealed how this unlikely combination could force an insect to pollinate the flowers. Near the base of the interior the hood petals fold in and the labellum widens to seal the chamber containing the column tube.

In the cross-section below the labellum is closed, but if you picture it leaning forward, imagine a male gnat crawling down it, following the plant-made scent of a female (pheromone).

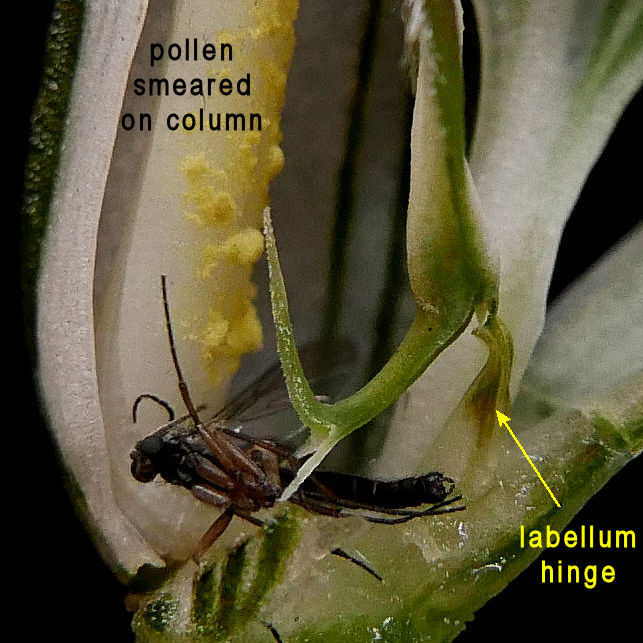

When the gnat get to the base, the labellum snaps forward, forcing it to climb the column (leaving behind pollen attached its body), through the tube where it gets another dose of pollen, and out of the flower.

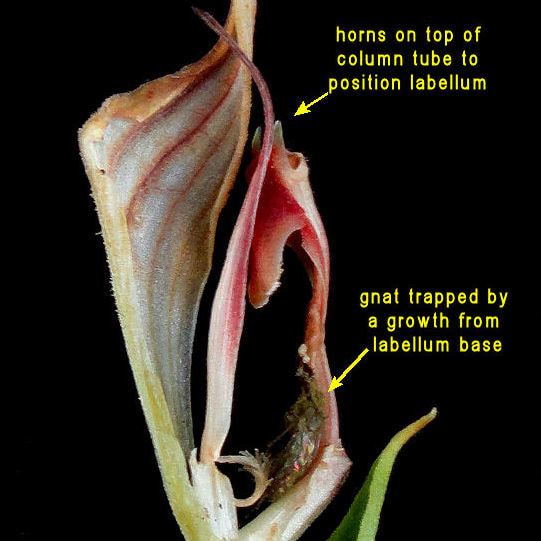

Can you see a gnat that was trapped by a curly bit at the base of the labellum? It is the remains of a Fungus Gnat (rather appropriate that it has been consumed by a fungus), whose maggots consume mushrooms, but more of this below.

It has the same infolded petals and thin labellum with widened base and little horns at the top of the column tube to position the labellum when closed.

An associate doing a PhD on greenhood orchid pollination agreed with me that evolution rarely produces intricate structures like this for no reason, but said that insect deaths may be collateral damage if the plant is successfully pollinated anyway. Is the hook just a fancy counterweight?

In the image below the column is smeared with pollen, so other gnats had been safely through this flower before this poor individual met its end.

However the mouldy gnat in the shell orchid reminded me that orchids require fungi to form a mycorrhiza. IF the mould spores could serve this purpose, this would be a neat way for these orchids to inoculate their seeds.

Who knows?