Recently I climbed Yilliminning rock in the evening which is a great time to gain an understanding of its formation. There is a great story in the rock itself if you look closely.

Most continents in the world consist mainly of granite (a light coloured quartz and feldspar rich rock that crystallised out from molten magma (igneous rock). The continents are separated by black dense crystalline rock (a bit like dolerite used for road building) that underlies ocean floors.

That the granite here formed over two thousand 6 hundred million years ago (your ancestral line may have been bacteria then) when two geological plates were colliding. As one slowly slid underneath the other it was forced into deep molten rock of the mantle and gradually melted.

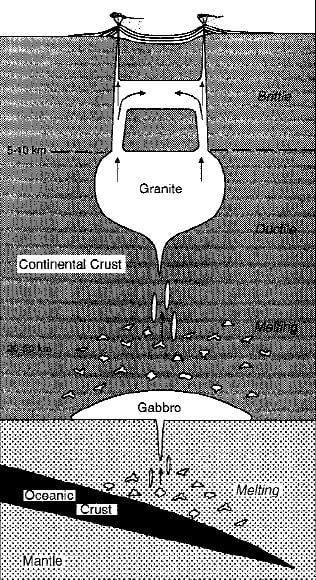

Being lighter, large domes of molten granite gradually forced their way upwards. They moved upwards through solid rock by “cauldron subsidence”. Intense heat from dome magma causes rock above to fracture and fall into the magma, creating a chamber that the magma moves into. Fractured rock from top and sides is often incorporated into the dome as partially melted xenoliths.

If they reach the surface, volcanoes spew out a fine grained granite like rock called andesite. However most times the domes stop two kilometers (km) or more below the land surface and gradually solidify into granite. You can tell that it cooled slowly because granite has large evenly spaced crystals.

Just think about it. As you stand on the top of Yilliminning Rock, you are 2 km below an ancient land surface.

The diagram on left shows ocean crust melting in the hot mantle after it has collided with and been forced underneath a continent. Molten material separates into dense black gabbro and lighter granite that rises towards the surface of the continent by cauldron subsidence.

If you wander over the surface you can see the relatively uniform speckled pale crystalline granite.

But look carefully, and you will see more.

Yilliminning rock contains lots of roughly north-west/south-east corrugations that are easily seen at dusk as shadows define them. Simplistically, I think that these could be due to slight differences in rock composition from

- Magma intruding cracks in the cooling rock.

- Changes in crystal size and possibly mineral composition that occurred due to temperature and pressure changes as the granite slowly cooled while still molten.

In winter, cracks expands as water in them freezes. Voila, a great home for Ornate Dragon Lizards (Ctenophorus ornatus). Eventually gravity and vibration/ pressure from earth movements (or more commonly humans) causes these sheets to break off and move downslope (or be crushed or carted away by humans!)

The image below shows granite structure in a broken sheet