Fossils have also been reported at Gracetown and the Pinnacles.

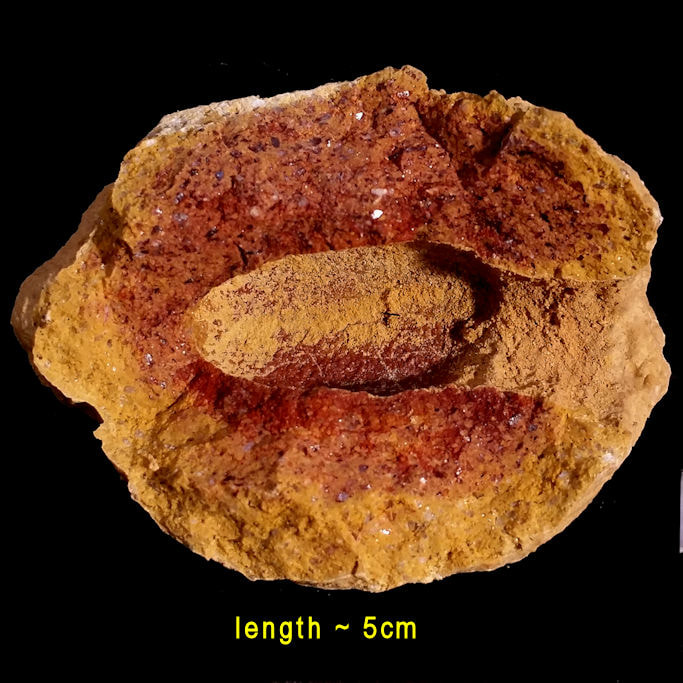

Leptopius larvae are grubs that feed on acacia roots in sand dunes before compressing an space in the soil and secreting liquid to make a case in which to pupate. After pupation the adult weevil makes a hole in the pupal case and digs its way to the surface. Over time the residual cases became cemented by a lime in the soil water.

Mukinbudin specimens are similar but chunkier and harder, and tend to have the exit hole at the end rather than the side.

I found a paper on fossilised Leptopius pupal cases in Weipa bauxite that look like those at Mukinbudin.

Clogs were lying everywhere, with more exposed ones in the process of breaking down. The number was mind blowing. Weevils have been pupating here for a very long time and still occur in the district.

The face of the pit showed about a metre of yellow loamy sand that then contained red- brown soft clogs and other nodules that became more numerous, harder, and paler with depth, then a layer of very hard pale silcrete rocks. Under this was the base of an ancient laterite showing root channels and that has been converted to a hard silcrete.

My guess is that hundreds of thousands (to millions?) of years ago a gravelly laterite upland similar to today’s Western Wheatbelt/ Darling Range formed here, when the climate was much wetter.

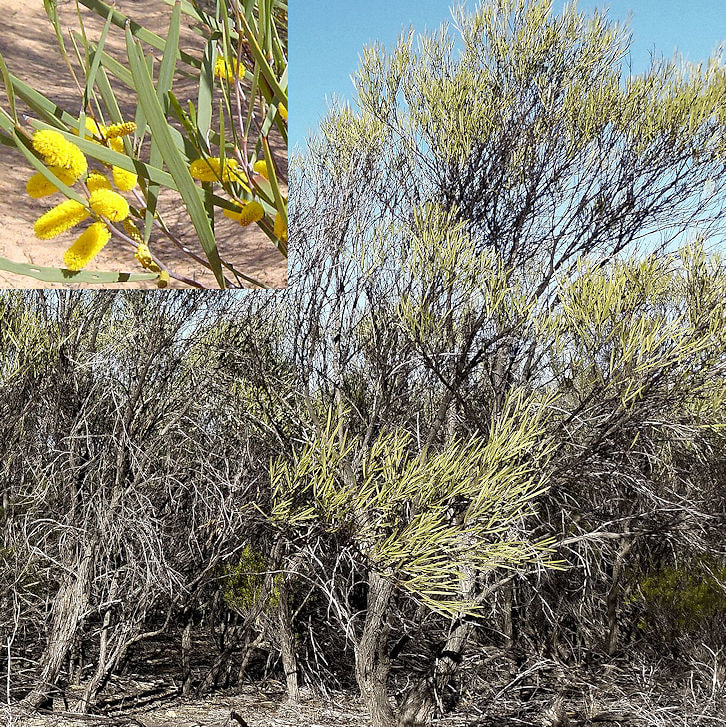

Over time in a drier phase the laterite was converted to a kwongan sandplain containing acacias, and generations of Leptopius larvae pupated in the soil. I suspect that the compacted soil on the edge of the pupal case acted as a wick for soil water and a nucleus for iron and aluminium mottles that preserved them.

The iron and aluminium was concentrated by cluster root species like proteaceae on today’s gravel soils or more likely casuarinaceae like the tamma shrubs that replace proteaceae in drier areas.

All clogs are filled with loosely cemented same size sand as the shells, so I guess that sand gradually trickled in the entrance as the shells hardened.

Acacia are very adaptable. They have root nodules that can produce nitrogen from the atmosphere like legumes. Wodjils also repel other species by making the soil very acidic and apparently secrete silica at depth, presumably to produce a barrier to prevent soil water from moving deeper than their root systems. Silica deposition below the mottled layer has created the exceptionally hard clogs.