There are a number of Diuris species In this district, but several are difficult for average person to separate. For simplicity I put them into three groups.

- Donkey orchids (most common) D. brachyscapa Western Wheatbelt Donkey Orchid, D. corymbosa Common Donkey Orchid, Diuris porrifolia, D. setaceae Bristly Donkey Orchid (at Newman Block).

- Bee Orchids D. decrementum Bee Orchid, D. laxiflora Common Bee orchid.

- Purple Pansy Orchid (Tarwonga Road) D. longifolia.

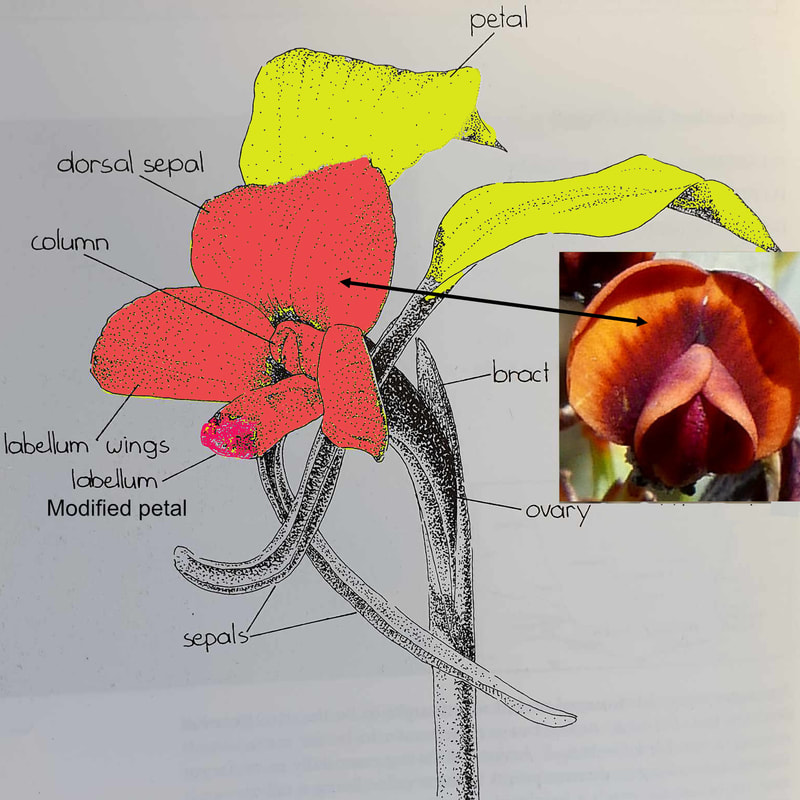

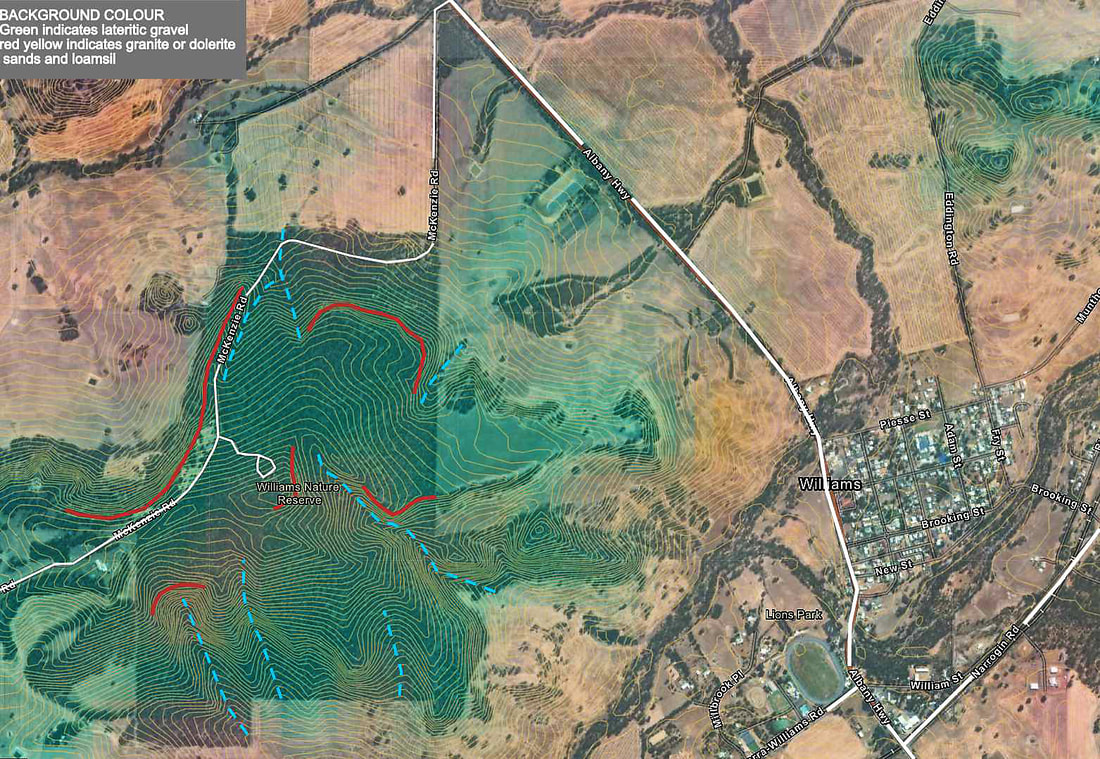

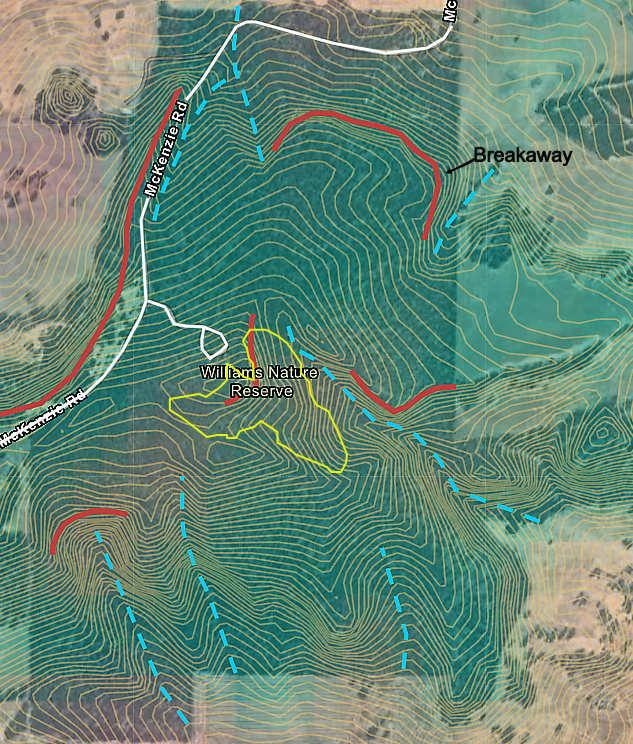

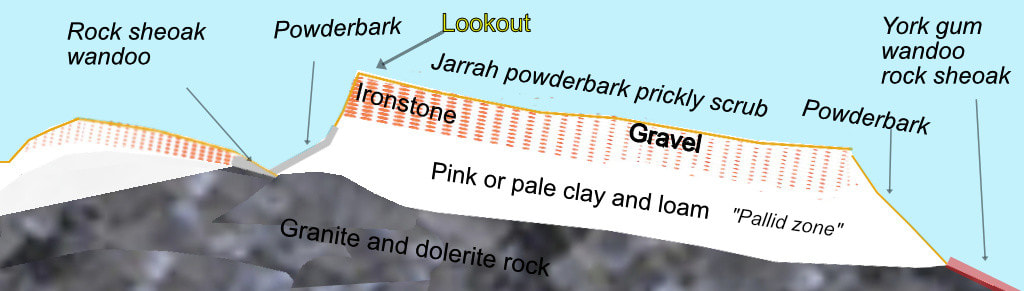

| This interesting (and very detailed) research paper describes how Diuris brumalis masquerades as a Daviesia pea flower so solitary native bees will pollinate them. The bee genus is Trichocolletes, pea flower specialists, which resemble imported Honey Bees, but fly faster and more erratically. Bees associate the Daviesia shape and colour with a nectar reward, and female bees also collect pollen. I coloured the diagram to show how shape of the central part of the Diuris flower resembles a Daviesia flower. colours are similar, but bees do not see the same colours as we do. In addition, bees can see ultraviolet light, which parts of the flower reflect to make them appear brighter (to bees but not us). |

The researchers measured equal numbers of Tricocolletes and honey bees visiting Diuris brumalis in the Perth hills, and departing with the same number of orchid pollinea on their head. However honey bees were much less effective in transferring pollinea to the orchids to pollinate them This is another example of possible negative effects of honeybees on biodiversity.

Further Reading: Footprints in the Pollen